Introduction by Jane Rossington who opened the programme, as Jill Richardson, in November 1964 with the line ‘Crossroads Motel, good evening…’

Introduction by Jane Rossington who opened the programme, as Jill Richardson, in November 1964 with the line ‘Crossroads Motel, good evening…’

“Crossroads was the brainchild of Reg Watson who worked for Lew Grade, boss of ATV, and Reg came up with this idea of doing a daily soap.

“By then we’d got Coronation Street which was slightly grand and called itself a drama series, and it aired twice a week. Reg felt there was room to have a show that was totally believable about everyday people in the Midlands.

“The reason ATV originally started it was because ATV was a regional network [for the Midlands weekdays and London at weekends] and it had to have some programming from Birmingham. The regulator required so many hours of local programming per week, and that’s why they started Crossroads as it filled two and a half hours of the schedule.” – Jane Rossington

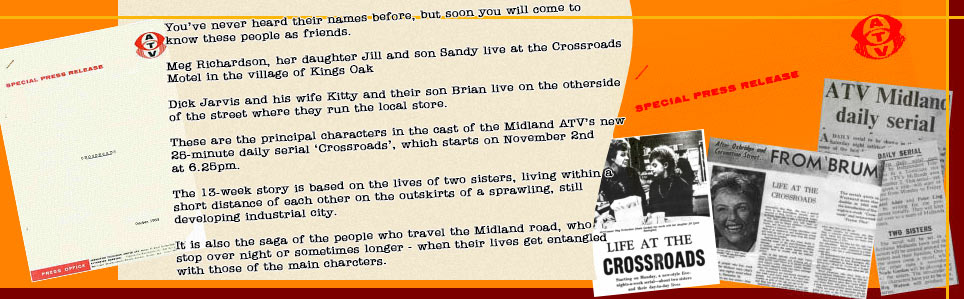

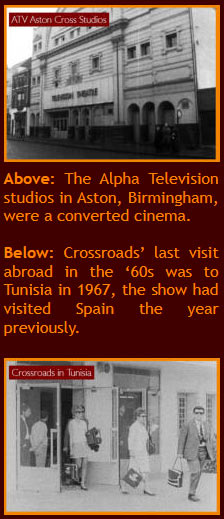

November 2nd 1964 and at 6:30 pm the very first monochrome edition of Crossroads was transmitted from the Alpha Studios in Aston, Birmingham; which were shared between ATV and ABC Television, with ATV transmitting Monday to Friday and ABC across the Midlands at weekends. The biggest studio at the complex was actually an old ABC cinema auditorium; this is where most of the programmes – including Crossroads – were made. The first six weeks were only shown on ATV, Border and UTV.

Westward TV and Anglia Television were the next two stations to air the soap from December 1964 onwards. Most of the IBA regional Network started showing the series from January 1965.

Westward TV and Anglia Television were the next two stations to air the soap from December 1964 onwards. Most of the IBA regional Network started showing the series from January 1965.

Tyne Tees Television had a brief spell of screening the soap in 1965 but dropped it after a month while Granada Television waited until the 1970s before even trying it. However the journey to get Crossroads on-air began a long time before 1964; in fact, Reg Watson first mooted the daily serial suggestion to ATV’s boss Sir Lew Grade in 1959, as Noele Gordon noted:

“In those days I used to be a hostess on ITV’s first Midlands chat show, Lunchbox. We had a resident team and I had celebrities to interview. The show was produced in ATV’s old Aston Road Studios on the outskirts of Birmingham and it had a big following.

“As the show grew more popular we used to take it out on location. At our first outside broadcast, Sir Lew Grade watched the programme in his London office beamed to him directly by landline from the Midlands. All our shows were live, nothing was recorded, so the idea of taking a live TV programme on tour immediately appealed to Sir Lew’s show-biz know-how.

“What really impressed him were the 27,000 fans who turned up at Nottingham Forest football ground to see the programme. We were expecting 3,000. When I walked out on the pitch they gave me the kind of cheer you usually only hear at Wembley… …It was this quite unexpected reception that I had from those warm-hearted folk that made Crossroads possible later on and I will always be grateful to them.”

It was these Lunch Box specials that caught the attention of Lew Grade, who wanted more of the same. However, the technical impracticalities made it impossible for ATV in the Midlands to produce a daily outside broadcast. The studio was underfunded and understaffed. Reg had another idea and told Lew that while ATV didn’t have the staff or facilities to expand Lunch Box, they could use the star of the show to create a potential networked success. Knowing of Noele’s West End Theatre and previous film acting parts he suggested her for a daily serial.

“You mean like those American evening soaps?” Lew asked. “No” replied Reg, “I don’t mean an evening soap opera. They only go out twice a week. I mean a real daily serial. Like the American daily daytime soaps.” Prior to ATV London, and ATV Midlands, launching in the mid-1950s both Reg Watson and Noele Gordon had ventured to America to study the commercial television services stateside.

Noele spent a year studying the medium at New York University for ATV and also got hands-on experience working for a local station, while Reg Watson spent time making notes on the formats and production routines of broadcasters including ABC. From seeing a number of daytime hour-long soaps, including sagas such as As The World Turns and Guiding Light, Reg first thought a daily UK serial would be a great idea.

Crossroads wasn’t the first daily saga attempted in the UK however, although it is the first to fill the full half-hour slot. When the IBA network launched in 1955 (as the ITA service) the daytime schedules saw the addition of a ten-minute daily serial, Sixpenny Corner. It, however, along with daytime broadcasts at that time, proved unsuccessful for production company Rediffusion London.

Back in the Midlands nothing more was said on the subject of a daily serial for ATV for over five years, but Lew Grade hadn’t forgotten – as Noele Gordon continues:

“On an August bank holiday, I had a phone call at my house at Ross-on-Wye from Philip Dorte who was then ATV’s Midlands Controller. I was just leaving to go to Birmingham to appear on Lunch Box.

“‘Nolly,’ he said, ‘I want to see you. Can you drop in on your way back from the studios?’ That evening I stopped off at Philip’s home and the first thing he did was to give me a drink. ‘I’ve got a shock for you,’ he said. ‘They’re taking off Lunchbox.’

“I felt myself go a little white. There was a sinking feeling in my tummy. Lunchbox had been my life for eight years. It was a terrible blow to suddenly hear it was all going to end. I was so stunned I scarcely heard Philip’s next words, ‘But don’t worry, its going to be replaced with a new half-hour daily serial, and you’re going to be the woman in it!’

“I sat down. I couldn’t believe what I had heard…The idea of producing a TV drama serial [for 30 minutes] every day had never been attempted [in the UK].”

The initial format for the serial came from a twice-weekly saga outline submitted to ATV Midlands by Birmingham Mail journalist Ivor Jay. Set in a Birmingham bed and breakfast the story followed two sisters who ran the establishment. Lew Grade liked the idea – especially as the television regulator was continuously complaining about ATV’s lack of regard, or dedication, to the Midlands.

A serial from the region to the network would show the company as committed to the Midlands, he believed. Hazel Adair and Peter Ling, who were at the time writing twice-weekly Compact for the BBC, were drafted in by Lew Grade to write the series. However they were not keen on taking on another writers idea, so suggested they come up with their own.

“We spent a busy weekend, working on ideas; the boarding house setting didn’t seem very attractive. At that time I lived near Brighton and Hazel lived near Dorking, and I suddenly remembered, on one of my cross-country journeys, I’d driven past a signboard advertising the opening of a new ‘Motel’ …I had a rough idea of what Motels were, from various American movies, but this was the first one I’d come across in England.

“Hazel warmed to the idea; at least it would be something new and different, and might even have a touch of glamour. So we worked on a rough outline, suggesting that the Motel should be run by a friendly middle-aged widow with a couple of growing children – and we jotted down ideas for possible storylines, involving various guests who would come and go.

“On Monday morning, we went back to ATV as soon as the office opened, and found Lew already behind his desk – he began work early every day. He lit another cigar and read the whole document in silence, while Hazel and I crossed our fingers. At last, he put the outline down and said simply – ‘OK – you’re on.. we’ll do yours.’

“In the beginning, Hazel and I worked together on the storylines and a good many of the scripts, but as Compact was still running, we had to divide our forces in order to keep our sanity – and although we churned out each week’s quota of storylines, we soon collected a small team of writers, who followed our storylines and worked on the scripts, dialogue, stage directions, etc.” – Co-creator Peter Ling

Keeping the sister idea they transformed it into The Midland Road, following a widower who had opened a motel in the grounds of her well-to-do home and her sister who struggled to make a living with a newsagents store and a recently unemployed husband.

The two sisters also had a brother, who was a sailor and would visit the village from time to time. Lunch Box producer Reg Watson was the obvious choice as the show’s boss, especially as Lew wanted the programme to air daily – which Reg had suggested all those years earlier.

Just before the show went to air a search was on for a new name. The Midland Road didn’t appeal to ATV’s head of programmes Bill Ward and the local press failed to come up with anything better following a competition for ideas. In the end, the prize money was given to a charity and Reg Watson came up with the Crossroads title.

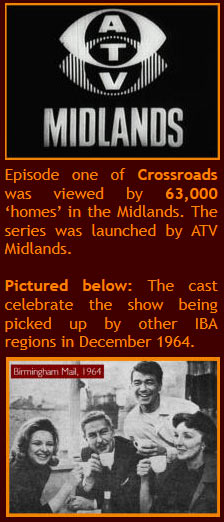

Each episode would switch to and forth from each family seeing how their respective lifestyles would affect their relationships. Noele Gordon played Meg Richardson, the motel owner; Beryl Johnstone played Kitty Jarvis, the newsagent. To reflect this the theme tune, composed by Tony Hatch, would have two slightly different variations and the show opened either with Meg’s Theme or Kitty’s Theme, depending on if the establishing scene was based at the motel or in the village.

Each episode would switch to and forth from each family seeing how their respective lifestyles would affect their relationships. Noele Gordon played Meg Richardson, the motel owner; Beryl Johnstone played Kitty Jarvis, the newsagent. To reflect this the theme tune, composed by Tony Hatch, would have two slightly different variations and the show opened either with Meg’s Theme or Kitty’s Theme, depending on if the establishing scene was based at the motel or in the village.

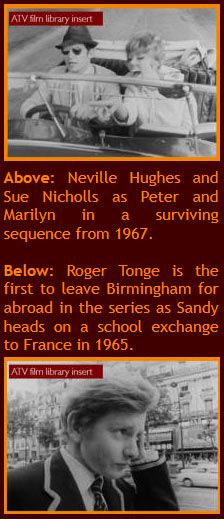

The very first episode opens in the reception area of the motel with 18-year-old Jill Richardson, (Jane Rossington) answering the motel telephone. “Crossroads Motel, Good Evening?” Jill is the daughter of Meg Richardson, the motel owner. Meg has a son Sandy (Roger Tonge) who at the time is still at school and is 15.

The first episode is not the opening of the motel; we learn that Meg inherited the land from her late husband Charles, in 1960, and had the motel added onto her Georgian home when a motorway was built next to Kings Oak. The motel opened on April 17th 1963. As time went on the motel side of the series became more dominant, although Kitty still appeared as one of the main characters until 1969, and her family featured for some years after. The cast grew year on year, but Noele, as Meg, took the leading role – so much so that whenever she didn’t appear in an edition a large number of viewers would call ATV to ask why eventually often if Noele was not to feature in an edition a throwaway reference to Meg was included to keep fans happy such as “she’s still shopping in Birmingham, she’ll be back later”.

Crossroads was never networked. For its entire original run, it was sold to each IBA company on a region-by-region basis. However, it proved a popular buy with most IBA regions as it pulled in over the average ratings for any slot it aired in.

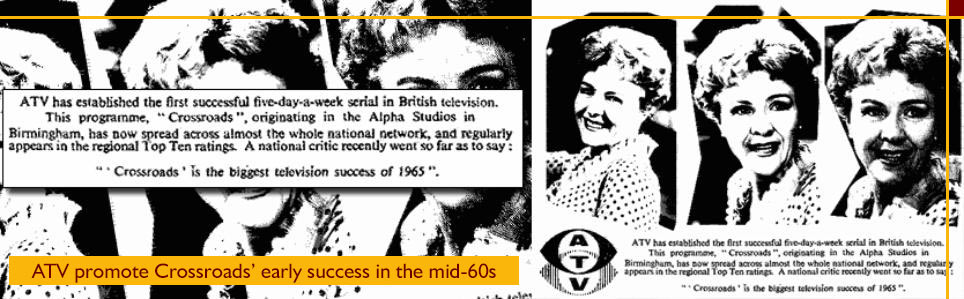

“Cheers! We’ve made it! The Crossroads cast toast – in coffee – to the network recognition of the six-week-old series. The first 50 editions of Crossroads have only been shown in a handful of regions, but the astonishing success of the first few episodes have lead to other regions booking the show.” – Birmingham Evening Mail, December 14th 1964

In 1965 Crossroads was described as “the biggest television success of the year” by one telly critic. This year also saw the serial, record with a film unit, overseas scenes on two separate occasions. Firstly in Paris where the character of Sandy went on a school visit and later Torremolinos with Spanish Chef Carlos and a few other motel regulars.

The series was also one of the first to use OB trucks and videotape for outside ‘serial’ recording as these 1965 production notes show from a session at Walford Hall and Baschurch Village. In September 1966 Crossroads made its first major television landmark by reaching 500 episodes. The Crossroads cast went on tour, at each location they stopped at Noele Gordon met a real-life Meg Richardson, all of whom later enjoyed a celebration dinner in Oxford. 1966 was also the year Crossroads was voted ‘ITV Programme of the Year‘ by viewers. An award ceremony saw producer Reg Watson pick up the gong. The series won the same gong in 1967, the same year Noele was also voted ITV Personality of the Year.

Oddly despite the success comparisons were already being made between Crossroads and other twice-weekly series such as Coronation Street and Emergency Ward 10. The twice-weekly shows were slightly more polished in some production values and certainly scripting, which wasn’t possible with a five-episode per week saga. While a programme which made two and a half hours of television a week should never have been compared to one which made only an hour a week, it was.

Critics knocked wobbly walls, which had been confined only to the first six months when the programme was only destined to run a few weeks and ‘theatre flat’ style sets were used. These were replaced in 1965 by industry-standard sets which every other serial and drama used – so they wobbled no more than the sets seen on Corrie thereafter. (Episode 126 is currently the only that survives with the original ‘wobblier’ sets – and it doesn’t appear to sway!)

“After two years I succumbed to the continual barrage of critical attacks. I wanted to take it off, but Lew wouldn’t let me. Lew was right, of course. I wanted the same standards set for Crossroads [as Emergency Ward 10].. ..but it wasn’t possible, not with five episodes a week.” – ATV’s head of programmes, Bill Ward.

All the other serials (none were called soaps) of the day produced two editions per week, with more money for each episode: What money they were putting into those two programmes, Crossroads had to spread across five. So the ATV series did seem of a lower budget, and of course, more episodes meant less rehearsal time and the ‘factory pace’ of production often made scripts far lower in standard than other sagas.

“Why Crossroads used to get stick was it was on five times a week and when you’re on five times a week, of course, you can’t neaten it up and tidy it. I’m amazed and very impressed in the way that they did it” – Coronation Street’s William Roache, Late Night Line-up, 1985

But contrary to the spin the press and other IBA stations put on it, this was not always the case with every edition. There were some outstanding scripts and scenes as well as the sometimes iffy ones. As Sir David Jason, who appeared in the soap early in his career, noted in his autobiography ‘My Story’ on the accusations of bad acting, wobbly sets and poor scripts:

“Of course that’s a terribly sweeping generalisation about a series which a lot of the performances and storytelling was really good. In defence of the production staff and the cast, most of the show’s failings to hit the mark were the result of hitting everything in a blind hurry, the series was running at a heart-attack rate of five half-hour episodes a week…

“And yet, for all that, it was a big hit. A television juggernaut, massively popular, the ITV network’s second watched show after Coronation Street and sometimes even capable of nudging ahead of it in the ratings.”

Actress Jan Todd also noted:

“The great thing was that, unlike Play of the Week, if something was not so good in episode one you could always try to do better with episodes, two, three and four.”

The fact the saga was recorded ‘as a live show’ caused a lot of stress to the cast: if they made a mistake it meant the whole part of that episode had to be re-done. If an actor messed up their lines in the final scene of part one, all the scenes in part one had to be re-recorded right from the start. Actors also had to learn for each episode two versions of the same script. There would be the ‘long version’ and the ‘short version’. Depending on whether the show was under or overrunning the script would switch from version to version as needed.

This never-ending, and stressful, workload lead to Noele resigning from Crossroads in 1968, as she noted in her 1975 autobiography from Star Books:

“The time-table which Reg had devised was ingenious and demanding. At the end of each day I was so tired I could hardly find the energy to talk and I’m sure it was the same for the rest of the cast….

“We used to get every Sunday free, but that’s all. And by free I just mean away from the studio. During this ‘freedom’ most of us were still learning our lines… When I walked out on Crossroads it made headline news, many people thought it was just a publicity stunt, but I assure you, it wasn’t. I really did resign and as far as I was concerned, Meg Richardson was finished; she and I were through.

“I had been with the serial for more than three years. We were all working very hard and it seemed to me that I was working hardest of all.. ..The new contract I had been offered was no different to the last and as I hadn’t had an increase in salary for seven years, I decided that if I was going to quit, this was the moment.”

Noele sent her letters of resignation to Head of ATV Sir Lew Grade, Programme Controller Leonard Mathews and Producer Reg Watson. The Sunday Telegraph found out what was going on and printed the news on their front page, other newspapers soon followed, this resulted in the ATV switchboard being jammed with unhappy fans and thousands of letters asking Noele to stay arrived at the studios.

One woman wrote ‘Don’t let Meg die; if you do I’ll kill myself.’ The Crossroads writers wrote Meg’s final episode – to be aired in the second week of August 1968. ATV promised Meg’s exit would be a dramatic departure. This news resulted in huge protests outside ATV – the company finally had to admit, Crossroads was one of the most popular programmes on television – and it was popular because of Noele Gordon.

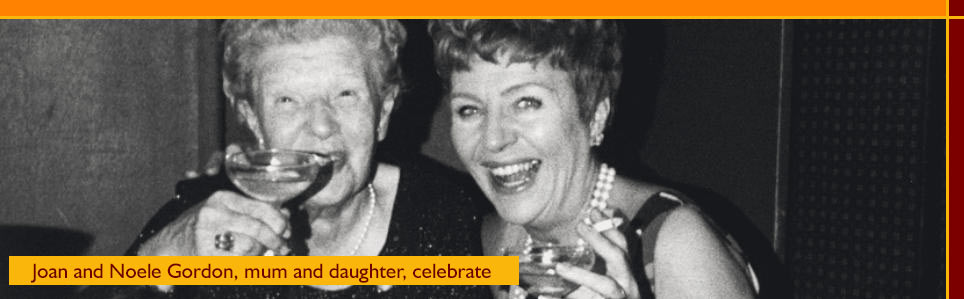

Round the table talks took place and in the end Noele, Lew and Reg agreed to a more reasonable contract, which also, as well as a better pay deal, saw Noele only appear in three episodes a week out of the then four made. Meg was to stay. “I went home to tell mother, hugged her, and we celebrated with a glass of champagne.” Said Noele.

1968 also saw changes to the ITA regional companies. Rediffusion, which had happily screened Crossroads since 1965, was replaced with Thames Television on London weekdays. In the same instance, ATV London had also been dropped to make way for LWT.

When Thames TV took over bosses decided to ditch the former daytime schedule, and as well as many other changes, Crossroads was dropped from its slot. Former Prime Minister Harold Wilson was in power at the time and, unfortunately for Thames Television, his wife Mary was a huge fan of Crossroads. Noele Gordon noted,

When Thames TV took over bosses decided to ditch the former daytime schedule, and as well as many other changes, Crossroads was dropped from its slot. Former Prime Minister Harold Wilson was in power at the time and, unfortunately for Thames Television, his wife Mary was a huge fan of Crossroads. Noele Gordon noted,

“Scores of letters arrived at Number 10 asking her to intervene when Crossroads was dropped by Thames Television in the London area… Mrs Wilson found herself attending a film premiere with Mr Harold Wilson, and among the other guests was Lord Aylestone, Chairman of the Independent Broadcasting Authority which controlled commercial television.

“Mrs Wilson mentioned to Lord Aylestone that she had received all these letters.. ..and asked him if he could bring back Crossroads.”

Lord Aylestone pointed out that the IBA could not personally request the return of Crossroads but he did say that they could make Thames TV aware of the situation, and in actual fact, the television regulator, the ITA, had been receiving many letters and calls about the removal of the soap too. Thames Television themselves were also bombarded with letters and telephone calls from annoyed fans, indignant at the axing of the saga with their switchboard bombarded for seven days after the programme had been dropped.

Brian Tesler, then Programme Controller at Thames TV, decided to bring the show back due to the public demand. Crossroads, however, in London would now be six months behind the rest of the UK as they started with the next episode from the last one aired by Rediffusion.

Although the fans clearly loved Crossroads, television critics were not so sure, Kenneth Eastaugh, who wrote for the Daily Mirror in 1966 said;

“Everybody and everything moves in agonizing slow motion, dragging every petty incident to the point where it snaps and vanishes. The dialogue is woolly, the acting stilted, the directing stale, the result absurd.”

While Richard Afton in the Birmingham Evening Mail wrote a scathing article, credited to being one of the most insulting ever written about any programme for many years; up until the BBC launched Eldorado in 1992 and a low point on EastEnders in the mid-2000s anyway.

“The intellectual level of TV would be raised if that deep depression over the centre of England called Crossroads was to be set adrift in the highways and byways of the Midlands with a guide, map or compass. It might, with luck, get lost forever.

“This dreary soap opera, churning out its miseries and woes four nights a week, must be responsible for as much gloom in the households who watch the show as a Harold Wilson speech. More so, because sometimes Mr Wilson is very funny; although he doesn’t intend to be.

“The stories are trite and the situations contrived. Whenever they can they resort to the juvenile gimmick of terminating an episode with a cliff-hanger similar to the Saturday afternoon serials at the pictures fifty years ago. It would be difficult to find a worse acted show on TV than this one.

“Tired Sandy, with the weight of the world on his shoulders, drones on in his monotonous whining way and never smiles. As for the scandal-mongering Amy, she should join the other two old ladies locked in the lavatory. It would stop her tongue wagging for a time and she might even learn her lines. Lording over it all is Saint Meg. I am sure she will be canonized someday… she is just so good and saintly to be true. In these troubled times, do viewers really want to be subjected, month after month, to the sordid misfortunes of fictitious people? Are we so sadistic?”

Of course, all these TV critics were long forgotten while Crossroads continued to be popular, and those who knocked the show in most cases never watched it long enough to make a reasoned opinion. Noele Gordon noted, ‘to get a picture of the show you have to watch a long run, not just one or two episodes now and again.’ Generally, ATV management and the cast took the view that those who knocked the show really insulted 16 million nightly viewers rather than the crew; which is a lot more viewers than many acclaimed shows have had watching. The programme also became loved, which many top-end large budget programmes failed to become.

But for Fleet Street, it seems Crossroads was too American for the TV critics. It was also too middle class. To date, it has been the only successful middle class ‘soap’ in the UK. As actress June Whitfield, who starred in middle-class suburban sitcom Terry and June, noted on critics; “They don’t like middle class, middle of the road, happy, harmless programmes.”

When in 1965 Tyne Tees Television in Newcastle decided to drop their weekday visits to the motel, the local critic in the Evening Chronicle was delighted by the news, although not so happy that the serial had been replaced with American programmes of ‘the same quality’.

Crossroads was set in an American devised motel, based on an American format and it was seen lowering television to the ‘level of the stateside offerings’ by some in the press. It was soon a regular talking point for the TV columnists each contradicting themselves with outrage that ‘nothing ever happens’ in the shows setting of Kings Oak or ‘it is too sensational, with unbelievable plots.’ The show couldn’t win – it couldn’t be both!

The fact Coronation Street suffered the same occasional set problems or fluffed lines, only credited to Crossroads didn’t matter, Corrie was ‘very British, working-class, with all the right accents’ so it could get away with the mistakes. The Granada production was also defended and protected by a rightly proud company, ATV – other than Lew Grade – didn’t defend it. It was seen as a cheap filler so didn’t in the scheme of things really matter.

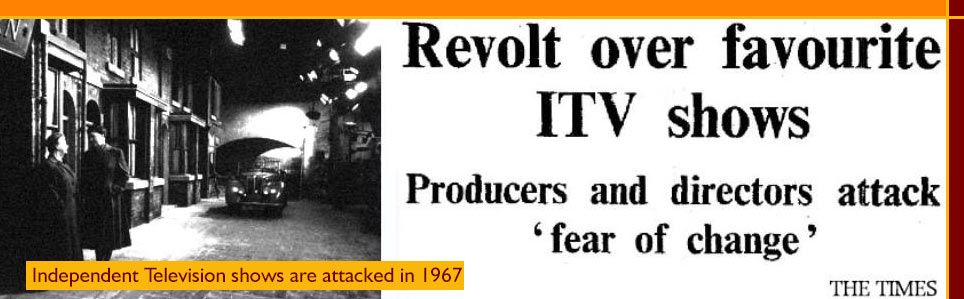

Unfortunately for Crossroads the television regulator seemed to be taking on board the views of the critics rather than the viewers and demanded in the interests of “quality” that the ATV production be dropped from five editions to four in 1967. The Independent Television Authority (ITA, later the IBA) suggested that the vacant Crossroads slot could be filled with something more informative. It was filled with cheap game shows and imports.

In the same year as the cut-back, Crossroads recorded three months worth of scenes in Tunisia for a storyline, adding a touch of higher value production standards to the episodes of that time. During this era, the soap also regularly recorded scenes on videotape and film for location shoots. Sadly the VT recorded items have long been wiped, however many hours of the film footage survives.

These items show how the programme often ventured outside the Alpha studio walls for scenes including moments with Marilyn Gates and Peter Hope on a date in his car, brother and sister Diane and Terry Lawton visiting London, chef Carlos Raphael fighting in a factory with his twin brother Georgio, Benny Wilmott flying a light aircraft and the landmark moment Meg crashes her car into Vince Parker on his motorbike, trying to avoid hitting a cat.

The loss of an episode was taken after a protest by 400 television producers and directors who called on the Independent Television Authority to deal with the issue of ‘low quality’ programmes.

The Guild of Television Producers and Directors in a memorandum stated that some Independent Television programmes, “underestimate the intelligence of the viewer by being geared to the lowest common denominator of humour. taste; and ability to participate.”

The body noted key productions that they believed deserved criticism for falling way below acceptable standards. It may be surprising to learn Crossroads was not on the list!

The body noted key productions that they believed deserved criticism for falling way below acceptable standards. It may be surprising to learn Crossroads was not on the list!

They did however note game shows Double Your Money and Take Your Pick as well as twice-weekly sagas Coronation Street and Emergency Ward 10.

“This levelling down rather than levelling up has to be resisted by all in television, particularly as the BBC, short of money and anxious to demonstrate its ability to attract viewers in order to justify a higher licence fee, is subject to the same kind of pressures.”

The guild says pressure to maintain high audience ratings on Independent television keeps established successes on the air for so long that all life goes from them.

“Fear of change, the fear of losing viewers through innovation, leads to a sameness of programmes that ought to be resisted. It also leads to the same programme being shown at the same time on the same night of every week, thus giving an overall fixed image of Independent television viewing with little room for surprise and practically none for the unknown except for the off-peak periods.

“Finally the pressure of uniformity, the pressure not to offend viewers, the ITA, or the Government results in ‘blandness and self-censorship, pernicious vices for television producers and directors’”.

While Crossroads wasn’t listed the regulator decided, it seems, to show it was listening to criticisms and chopped some populist programming including axing the fifth edition of the motel saga. Another issue the ITA had always had since ATV Midlands went on air in 1956, was the company’s dedication to the region – or the lack of it.

The Alpha Television Studios was a former theatre, complete with a leaking roof. For years there were no ‘built’ transmission facilities; instead, an outside broadcast van was parked at the back of the cinema in order to get shows on air. The service was underfunded and understaffed. It was noted at one point Noele Gordon and Reg Watson had taken on a number of roles within the organisation in order to keep ATV in the region on-air while Lew Grade would pay staff in cash, in person, at the studios at the end of every month.

With the changes to the regional broadcasters in 1968, which saw ATV London axed, ATV Midlands was awarded a seven-day licence to transmit to the Midlands.

When granted, in 1964, it came with the stipulation that ATV would have purpose-built studios in the area it served. You would have thought that with the ATV Midland region originally being the company’s five-day service they’d have committed to the area. However Lew Grade was a showbiz impresario and London was his key location, so even in those days, London was the place they aimed to set up base, eventually settling with studios in Borehamwood.

However in 1969, the ITA-imposed ATV Centre finally opened, and Crossroads was the first programme to use the major studio one. Later in the year, Crossroads was also the first ITA serial to air a full episode in colour, when in November ATV replaced its monochrome service. It wasn’t until 1970 however that the studio was officially opened…

Next the 1970s…

| Page credits: written in parts by Mike Garrett, Douglas Lambert and Tom Dearnley Davidson.

Quotes: Noele Gordon from her autobiography, My Life At Crossroads by Star Books, June Whitfield on The Alan Titchmarsh Show, 2013, Bill Ward TV Times 1971, ITA complaint by directors/producers from ATV Archive. Sir David Jason from his autobiography My Story by Century Books, Peter Ling in a fan club interview in 2002 and Jan Todd in the TV Times. Photographs courtesy of Reg Watson, Central Press Office, Carlton Archive, John Jameson Davis and Peter Kingsman, Noele Gordon archive. Press cuttings courtesy of Reg Watson. |