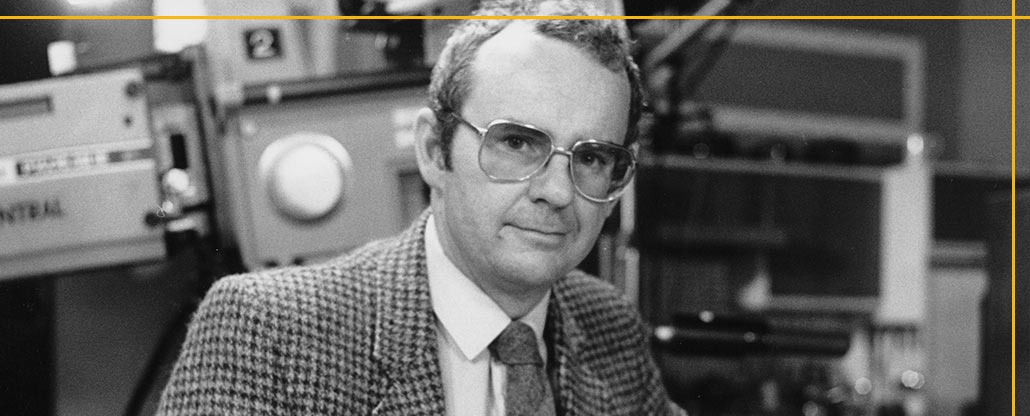

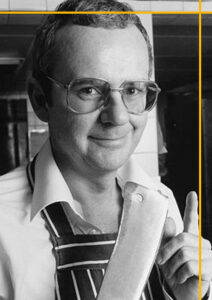

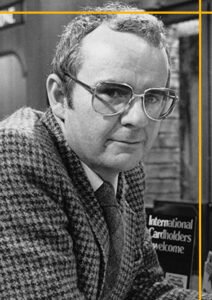

William took over as producer of Crossroads from Phillip Bowman in the autumn of 1986 and stayed with it until its demise in April 1988.

Can you tell us a little bit about your life before soap and how you got into the business?

I was a newspaper journalist, then a BBC journalist at Pebble Mill. I started writing historical plays for radio, then went as a TV script editor with English Regions Drama, also at Pebble Mill. There I was approached by The Archers, who were looking for a writer. After writing for the programme for 3 years or so, I was offered the job of producer.

You were credited for turning around the fortunes of the BBC Radio-soap, The Archers. Was it a difficult decision to leave that programme after such a lengthy and successful spell and move over to Crossroads?

Central’s Drama controller approached me about Crossroads before Phillip Bowman was appointed, but I was very wary. Ted wanted me to improve the quality of Crossroads and thus restore its fortunes. I said that with The Archers, I had taken on what was basically a Radio 2 (old light programme) show that was being broadcast to a Radio 4 audience that would welcome and appreciate something different.

I saw Crossroads as a far more difficult job. Here you had a programme that was self-evidently satisfying a large and devoted audience, but that was regarded by the press and public and every comedian in the world as being a low-quality ham-fisted joke. If you changed it, you would inevitably offend loyal viewers but the press and world at large wouldn’t notice because they didn’t actually watch the programme. So Ted went and offered the job to Phillip. Eventually, he came back to me. He said the “revamp” hadn’t done what they hoped, and he offered me the job of Executive Producer Drama Serials, which would include other programmes as well as Crossroads. But it was Crossroads they wanted me for, and in truth, Crossroads was the programme that interested me. It wasn’t a difficult decision in the end. It was a huge opportunity.

When you first took over as producer of Crossroads the programme had already undergone a quite recent huge revamp. How did you assess the situation when you took over and what did you feel were the main challenges?

As above, the same challenge as The Archers but more difficult. The task was to get the scripts right, get the production right, and then – most difficult of all – to persuade the press that it was indeed a different programme.

What changes were you asked to make to the programme by Central, and which were your own choices?

Central were unhappy at being the ITV company that made the serial drama with the lowest reputation, and which attracted an audience in the lower social groupings, which meant that advertisers would pay less to advertise in the Crossroads commercial break than in the Coronation Street break.

They gave me a free hand, on the understanding that I would move the programme “upmarket” so that it would attract the A,B,C (I think) type viewers (sorry I can’t be more explicit, advertising isn’t my field) that were happy to watch Coronation Street.

The replacing of the Tony Hatch theme tune. How did you feel about that? Did you see Kings Oak eventually becoming a totally new programme – without the hotel?

I thought a change of name, theme music and titles was – by this time – the only way to stop the programme from being unfairly and continuously dismissed as rubbish by people who did not even watch it. The plan was to broaden the story out, so that it became the story of an English village in the Midlands, with typical, recognisable Midlanders as characters, a hotel (motel), a shop, and a pub. Kings Oak is an excellent name.

I wanted the programme to genuinely, carefully, and humorously portray the life in a village south of Birmingham – in the way that Coronation Street was always proud to be a story of life in a Lancashire cotton town.

I believed that Crossroads suffered (and had always suffered) from a very basic structural fault that had over many years made it difficult to produce drama of high quality. The basic fact about any soap opera is that it gobbles up stories at a tremendous rate. This can only be done realistically if you have a number of individual homes (really just settings for individual stories) and a place where the people can meet when you want them to meet.

Thus characters from house 1 can be involved in a bitter divorce, characters from house 2 a comedy story, and house 3 a romance. When these stories have run their course you can move into stories involving houses 4 5 and 6. The characters can fade to the background naturally if you want them to. The story can be clear. When people meet it is because you want them to meet, and they can meet in a place (pub, shop) where the conversation is natural.

Setting everything in, and involving, a hotel makes everything so much more difficult, and so much more forced. When I took over Crossroads there was a writer [Adele Rose] on the team who also wrote for Coronation Street. At the first script meeting, she said she was always puzzled because the scenes she wrote for Coronation Street came over as strong realistic drama, but the stuff she wrote for Crossroads always sounded embarrassing, awful and clunky – but she was the same writer, producing the same dialogue.

A major reason for this, I believed, was that the hotel reception was the biggest set and an enormous number of scenes were set in it. But in real life hotel staff do not hang around the hotel lobby having arguments, chats, romances, tiffs. So every conversation is unnatural and forced. The first thing I did was cut the reception set in half and build a staff restroom.

Another reason was the appalling standards of production at Central. Coming from BBC Pebble Mill I was shocked by studio practices. An example: Actors on a set often have to say lines – dramatic, passionate, emotional lines perhaps – addressed to another character but in truth looking out into the darkness of the studio with the various technicians doing their business. At the BBC every crew member in the actor’s “eye line” would know to remain quiet and still, to avoid distracting the actor.

On Crossroads the technicians would chat to each other about Villa’s prospects on Saturday. At the BBC even the most junior member of the crew knew never to wear hard-soled shoes in the studio. On the Crossroads set, they had no such rule. The first thing I did when we took Jupiter Moon to Central was to have a big notice placed outside the studio door, reminding all crew of professional studio discipline.

Can you sympathise at all with the long-term fans of the programme who felt all the changes made during the 1980s were un-needed?

The trouble is that Crossroads DID have an awful reputation for the quality of the scripts, acting, and production. It is the people who let it get this reputation (ATV presumably) who ought to be blamed.

Crossroads was axed months before the Kings Oak idea actually launched. The ratings after the 1987 revamp actually started to rise, and the targets Central had wanted for the show were met. Why do you think when the show was actually starting to become a success again it was axed?

It’s certainly true that I was brought from the BBC in order to “relaunch” the programme as Kings Oak, with new titles, a new theme tune, and a team of top writers – and then the programme was killed off before the “relaunch” had actually happened.

It’s also true that despite all the changes by Phillip, and then the even more drastic changes that I made, the programme was always more popular than Emmerdale. I think we were no 4 in the ITV top ten in the week we were axed.

I think it was succeeding because the structure was better, the new characters were better (and better acted) than those they replaced, and because there was much more humour in the programme. But I would say all this, wouldn’t I?

I know little of why it was axed. We had just been promised a weekend omnibus, as I recall. The view in Central was that Andy Allan surrendered the Crossroads slot in return for other slots that he badly wanted. When we talked, afterwards, he said, “Let’s face it, Crossroads was never going to win any awards”. There was a belief that he was so busy with other things that he was only dimly aware of the changes that were in the pipeline.

There are some fans who think Crossroads would have been fine if it hadn’t undergone so many changes in such a short time, do you think time was the main problem, and had all the revamps happened over a longer period the soap might have survived?

As I said above, I think the problem went back over many years. Why did Coronation Street have such a fine reputation, and Crossroads such a poor reputation? These things don’t happen by accident, or by act of God. Granada took pride, over years, in ensuring that Coronation Street had fine writers and high production standards. Yorkshire fiercely defended Emmerdale, and has spent decades trying to overtake Coronation Street.

Nobody at ATV, or at Central before Ted Childs came along as drama chief, cared about Crossroads.

It is said that crossroads was never looked on favourably by the “powers that be”. Do you think this is true and if so, why?

I think I’ve probably answered this. In the end Central were embarrassed by the programme. It had to be changed, drastically, or be axed. What I didn’t expect was that they’d bring me in to do the drastic change and then axe it before the change came into effect.

It wasn’t Ted Childs’ fault. He was as shocked as I was – he had brought me to Central in good faith.

What would you say were the highpoints of your time as producer? Which things did you think were most successful?

I thought the new characters, and the stories, were working as I had hoped. I thought we had pulled off many changes and kept the audience with us, and could go forward to build a new audience. I thought that we were producing a programme with better scripts and better acting that Coronation Street or EastEnders.

Were there any changes you had planned, but sadly didn’t get round to doing?

Sending Benny off forever to work at the donkey sanctuary…

I believe you knew Jack Barton through staying at the same boarding house in the early 1980s. Can you tell us a little about him?

I didn’t really know Jack. He was clearly a very successful producer, and delivered huge audiences. But I’m sure you know far better than I the story of Crossroads relative decline in audience terms and reputation.

Most fans seem to believe Central didn’t want Crossroads, so why do you think the press decided to blame you rather than the man who actually axed it, Andy Allan?

Because I was the name the public knew – and the tabloids had been running stories for months – “Butcher Bill” – “Barmy Bill” – so I was obviously the one to blame. I benefited from a similar situation at the BBC – it was the programme head Jock Gallagher who battled to keep The Archers from being axed in the mid-seventies – but I was the one who got the credit when it emerged as a success in the Eighties.

There was reportedly three endings recorded for those final moments of the last-ever edition. At the time the whole period was surrounded in secrecy. Can you tell us more of those ‘alternative’ endings?

I think this was all press invention.

What did you think when you heard that Crossroads was being revived in 2000? Did you feel that it ever had any chance of success?

No, I didn’t think it had any chance. It was nostalgia and yearning for those millions of viewers that Andy Allan so lightly chucked away. Andy himself is said to have regarded killing off Crossroads as his biggest mistake.

After Crossroads you were involved with many other popular drama programmes at Central, however the only one to gain a cult following is Jupiter Moon. Can you tell us about that show which you created for BSB?

British Satellite Broadcasting was starting up and looking for a new soap opera. Numerous television companies were in the running to make it, dozens of ideas were being sweated over. At Central Television I put together a long, detailed proposal. When I sent it off I added, for luck, a second idea for a sci-fi series that didn’t even fill one side of A4 paper – I called it: “Voyage Of The Ilea” The loves, passions, and courage of the students and crew of a space polytechnic as it ventures through the universe in search of scientific discoveries”

John Gau of BSB wrote back and said that he loved it. When we met he asked why the ship was called the Ilea. I said that in a dark dream I had imagined Ken Livingstone as a senior statesman, naming the first European space polytechnic in honour of the Inner London Education Authority, so cruelly killed by Mrs Thatcher.

John Gau said that the programme was a great idea and commissioned 150 episodes with a budget £6m. Dr Bob Parkinson of British Aerospace designed the spaceship and it was built in the Birmingham television studio that had, until recently, been occupied by Crossroads. “Beam me up, Benny” a Daily Star headline had once said, reporting that Benny was an alien.

Now it had come to pass – a spaceship landing on the motel. The spaceship set was the only accurately-scaled prototype of a spaceship interior in the world. NASA had a design on paper, but ours was the only reality.IBM offered to build the ship’s computer but pulled out because we wouldn’t agree that it would not crash if attacked by space monsters. What would people wear in 2050? The future was Katherine Hamnett and John Paul Gaultier, we decided, buying up entire collections.

The special effects were shot in Prague, where the Ilea model was 5 metres long. The superb music score by Alan Parker was recorded by the Prague Symphony Orchestra. It was chaotic, not least because the Czechs were in the middle of a revolution. As the Ilea sailed through space at Barrandov studios, students in the centre of Prague were raising the Czech flag over the statue of King Wenceslas. Communism fell while the Ilea battled in space with the pirate ship Santa Maria.

Our leading sci-fi writer was Ben Aaronovitch, one of the very best Dr Who writers, who came in with some superb storylines and scripts. Some of the writers had worked on Radio 4’s The Archers. They were daunted by the lack of countryside. While the sci-fi team wrote stories about computers programmed to murder and dangerous missions to volcanic moons, they wrote a gentle story about a hamster and another one about a donkey sanctuary.

The series sold for £2m to Germany, and we cast a German actor to play a young space-criminal, but when the actor came to Birmingham he didn’t like it and flew straight back to Munich. A promising, keen young actor, Jason Durr, was called up from London. He had to learn his lines, manage without rehearsal, have his hair crew-cut and died yellow, and perform the next day. To add to the problems we forgot to book him into a hotel.

Most of the cast were young, inexperienced, and amazed to find themselves sometimes earning over £1,000 a week. Several, like Jason, have gone on to great success. Anna Chancellor, now seen in prestigious dramas like Four Weddings and a Funeral and Tipping the Velvet auditioned with a terrible cold and high temperature, went back home to bed and was immediately summoned back across London in the rush hour to give a second, brilliant performance as cool, lovely Mercedes Page, space navigator extraordinaire.

Faye Masterson, now starring in US sci-fi films having been cast in a major role by Mel Gibson, was only 16 when she came to Birmingham to play new Ilea student Gabrielle. Lucy Benjamin, who has found fame in EastEnders, said the first line of episode 1 of Jupiter Moon and almost the last line of episode 150. Nick Moran, star of Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels came in to play the character Zadoc.

Providing names for characters was always tricky – what will be the in-names of 2050? Phillipe Gervaise was named after a chap called Ricky, who was the boyfriend of the associate producer. We thought we’d blow a little of the stardust of fame over him.

Jupiter Moon has been called “The Crossroads Motel in space!” How do you take to such remarks?

I didn’t know it had been called that, but I don’t mind.

Can you tell us a little about what you’re up to now in 2004?

We’ve got a 35ft motor cruiser and my main interest is in planning (the doing) voyages back and forth across the Channel, and through the French canals. My last bit of writing was a one-man play for Richard Derrington (star of Jupiter Moon) called Shakespeare’s Other Anne and a new edition of my book Writing for Television is coming out in February.

Interview conducted by Mike Garrett for the Crossroads Fan Club, 2004.